I saw 25 films at the most recent Cannes Film Festival, where Lukas Dhont’s friendship drama “Close,” the movie we’re watching tonight, won the Grand Prix. This was the only film there that made me cry.

I’ll tell you why in a moment, but first, let me quote the late Roger Ebert, a vital movie critic for many decades. He often referred to films as “the most powerful empathy machine in all the arts.”

“When I go to a great movie,” he said, “I can live somebody else’s life for a while.”

This is often true. I would argue not so much, though, in big-screen depictions of mental illness. Throughout movie history, the mentally unwell have often been presented as monstrous aberrations from cultural norms. Mental health workers, meanwhile, come across as judgmental and unhelpful.

This is not the case with tonight’s special screening: Lukas Dhont’s marvellous movie “Close,” the deeply empathetic and compassionate story of two adolescent boys and a friendship that suddenly fractures, with life-changing effects.

First, let me quickly survey the depiction of mental health at the movies over the past century, a progression I’ve dubbed “From Creep Show to Compassion”:

M (1931)

In Fritz Lang’s German Expressionist classic, Peter Lorre plays Hans Beckert, a psychiatric ward escapee. He stalks and murders children on the streets of Berlin, causing fear and mayhem among both the public and the police. Criminals are alarmed, too, since the high state of anxiety is bad for business.

Finally captured and paraded before a kangaroo court, Beckert roars, “I have no control over this, this evil thing inside of me, the fire, the voices, the torment!” Based in part on a true story, “M” presents the archetypal cinematic depiction of mental illness as an evil and fearful affliction — it’s been called the first psycho-thriller. Perhaps lost beneath the terror is Lang’s subtext: a plea for more treatment and justice for the mentally ill.

Gaslight (1944)

You’re familiar with the term “gaslighting,” wherein someone attempts to make you doubt your own sanity? It comes from this film by George Cukor, which won Ingrid Bergman a Best Actress Oscar. She plays Paula, the unknowing wife of a criminal and possibly murderous husband, played by Charles Boyer. He confines Paula to their home, insisting the strange noises she hears and weird occurrences she notices are due to a simple case of female hysteria. The trailer for the film seems torn from the pages of a Harlequin romance novel: “A story that reveals a man’s secret and unholy desires … and probes into the strange emotional depths of one woman’s heart!”

Psycho (1960)

Everybody knows about Janet Leigh’s shower murder in Alfred Hitchcock’s motel hell story, but how many recall the psychiatrist’s summary at the end of the film? It’s a rare move by Hitchcock to explain his horror, which some critics have derided as mansplaining. He felt the audience needed insights into the cross-dressing and homicidal behaviour of motel manager Norman Bates, played by Anthony Perkins, who murders while impersonating his dead mother. This is the most famous and shocking example of Sigmund Freud’s Oedipus complex on the big screen, and Norman’s mother had her own opinion about psychologists: she declared them to be “filthy.”

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975)

This was the first film since “It Happened One Night” in 1934 to win all five top Academy Awards: Best Picture, director (Milos Forman), actor (Jack Nicholson) and actress (Louise Fletcher). Set in 1963, Nicholson plays a Korean War veteran and criminal named R. P. McMurphy, who pleads insanity to get out of prison work duties. He lands in a mental institution under the unforgiving gaze and abusive control of Fletcher’s Nurse Ratched, whose name has become synonymous with unfeeling health practitioners. McMurphy leads a rebellion. “Cuckoo’s Nest” was hailed by both critics and audiences for fighting conformity. It humanized the popular view of mentally ill people but had the opposite effect on how healthcare workers were seen.

Girl, Interrupted (1999)

An early cinematic depiction of “borderline personality disorder” is James Mangold’s star-studded drama from the end of the last century. Set in the 1960s and based on a true story, it stars Winona Ryder as Susanna, a teenager with BPD who is sent to an institution for troubled women. She befriends a rebel named Lisa, a role that won Angelina Jolie that year’s Oscar for Best Supporting Actress. The film also stars Elisabeth Moss and Brittany Murphy as fellow residents, all giving performances hailed for their realism and humanity. Once again, however, medical staff are shown to be more bureaucrats than healers. The nurse played by Whoopi Goldberg displays some compassion, but when Susannah pushes her too far, she declares, “You are a lazy, self-indulgent little girl who is driving yourself crazy!”

Close (2023)

Now we come to tonight’s film, one I believe shows a welcome advancement in society’s thinking about mental illness.

“Something happened.” These are the words that cut through the apparent calm in the early going of “Close,” a sensitive depiction of boys growing up in a rural town in Belgium. What happens from that point changes the movie and the lives within it.

“Close” is the story of lifelong pals Léo and Rémi, played by newcomers Eden Dambrine and Gustav De Waele. They spend idyllic summer days in each other’s company and sleep close to each other like puppies. The quieter Rémi, a musician, spends much time playing the oboe. The more outgoing Léo helps out on his family’s chrysanthemum farm.

When the boys return to school after their summer break, challenges arrive. Léo and Rémi are teased and bullied for their close bonds. Léo starts to feel embarrassed and draws apart from Rémi as he seeks to prove his manliness by joining a hockey team. Rémi, feeling bewildered and betrayed, draws more into himself.

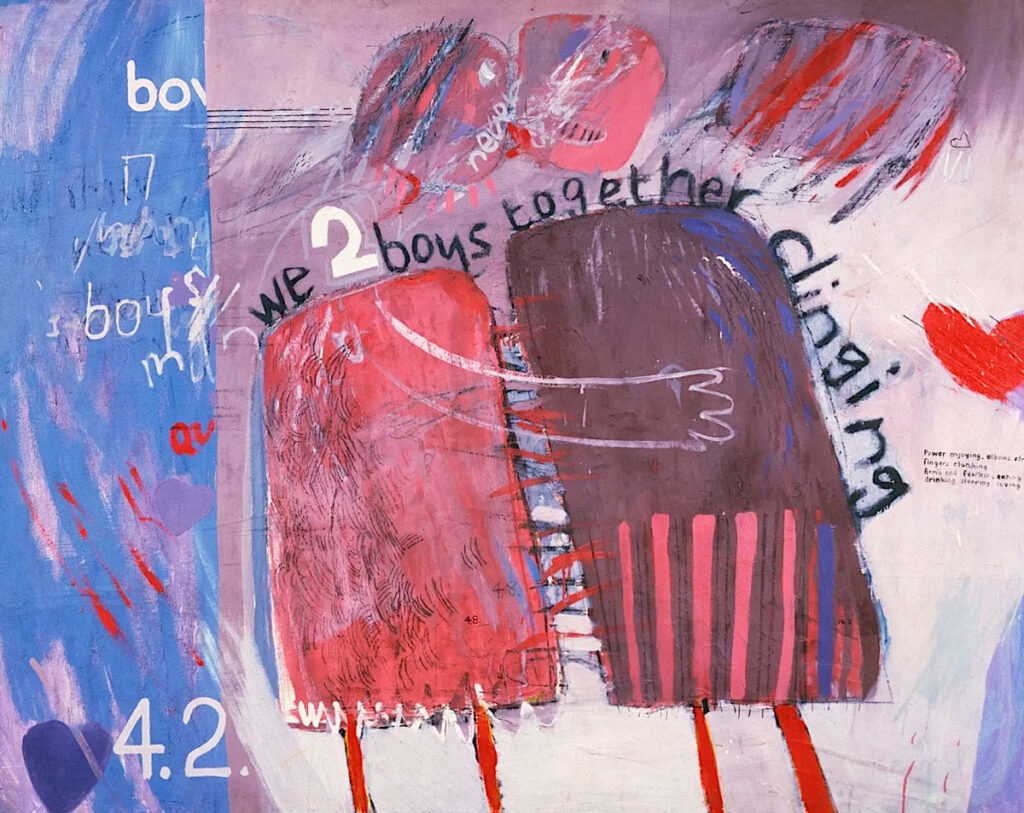

Dhont says his film was inspired by his own boyhood and also by a 1961 abstract painting by British artist David Hockney: “We Two Boys Together Clinging,” taken from the Walt Whitman poem of the same name. Dhont likes this painting so much he almost used it for the title of his film, instead of “Close.”

I saw aspects of my own life in “Close.” When I was 13, I had a dear friend named Mike who excelled at every sport. When I excelled at none; I was so bad at baseball, languishing in left field, both teams applauded on the rare occasions I caught a fly ball.

Mike became a captain and stopped selecting me for his teams. We drew apart and haven’t seen each for decades. I thought of him while watching “Close” at Cannes. Now you know why I cried.

I conclude with this classic cinematic advice as you watch “Close”: get out your handkerchiefs!

Eli’s Place will be a rural, residential treatment program for young adults with serious mental illness. To learn more about our mission and our proven-effective model click here.

Peter Howell | Friend of Eli’s Place

Movie Critic, Toronto Star | Past President, Toronto Film Critics Assoc. | Member, CriticsChoice Assoc.

Peter Howell has been the Toronto Star’s movie critic since 1996. He was the Star’s pop music critic from 1991-96. He is the Past President of the Toronto Film Critics Association, for which he was the executive producer of a Canadian Screen Awards-winning virtual gala in 2021. He is also a member of the Critics Choice Association and the proud Canadian member of the “Gurus o’ Gold” Oscars panel on MovieCityNews.com. His favourite film of all time is “2001: A Space Odyssey.” Blog: Nightviz.ca | Socials: @peterhowellfilm